How to outsmart the Smart City

Today’s digital world has created new ways to keep us all informed and safe while automating our daily lives. Our phones send us alerts about weather hazards, traffic issues and lost children. We trust these systems since we have no reason not to — but that trust has been tested before, says Daniel Crowley

“We found 17 zero-day vulnerabilities in four smart city systems — eight of which are critical in severity ”

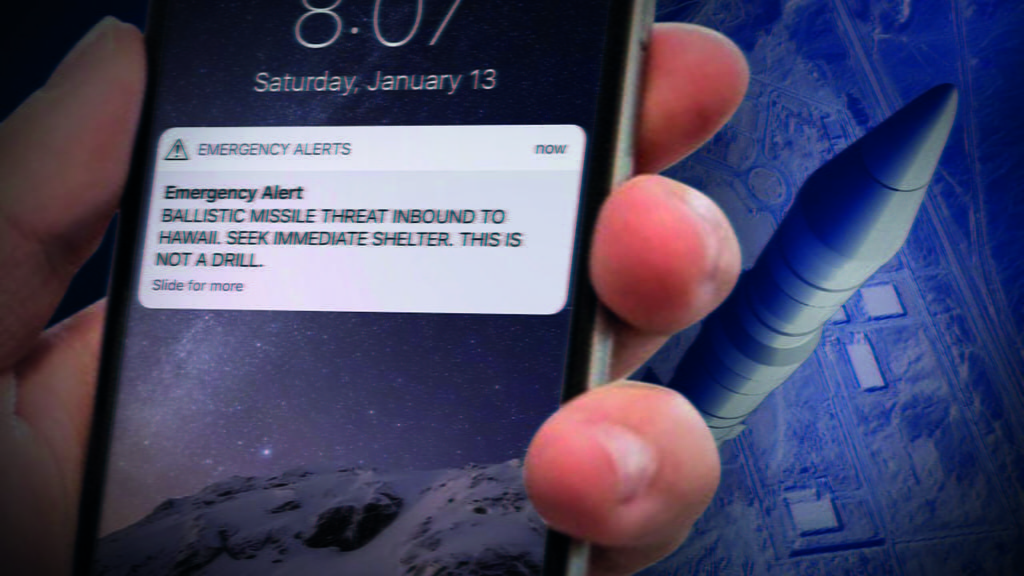

For a tense 38 minutes in January 2018, residents of Hawaii saw the following civil alert message on their mobile devices: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

It was not a drill but a false alarm that was eventually attributed to human error. However, what if someone intentionally caused panic using these types of systems? S

MART CITY VIEW

This incident in Hawaii was part of what motivated a team of researchers from Threatcare and IBM X-Force Red (led by the author) to join forces and test several smart city devices, with the specific goal of investigating “supervillain-level” attacks from afar.

We found 17 zero-day vulnerabilities in four smart city systems — eight of which are critical in severity. While we were prepared to dig deep to find vulnerabilities, our initial testing yielded some of the most common security issues, such as default passwords, authentication bypass and SQL injections, making us realize that smart cities are already exposed to old-school threats that should not be part of any smart environment.

So, what do smart city systems do? There are a number of different functions that smart city technology can perform — from detecting and attempting to mitigate traffic congestion to disaster detection and response to remote control of industry and public utilities.

The devices we tested fall into three categories: intelligent transportation systems, disaster management and the industrial Internet of Things (IoT). They communicate via Wi-Fi, 4G cellular, ZigBee and other communication protocols and platforms. Data generated by these systems and their sensors is fed into interfaces that tell us things about the state of our cities — like that the water level at the dam is getting too high, the radiation levels near the nuclear power plant are safe or the traffic on the highway is not too bad today.

SMART CITY VULNERABLE

Earlier this year, our team tested smart city systems from Libelium, Echelon and Battelle. Libelium is a manufacturer of hardware for wireless sensor networks. Echelon sells industrial IoT, embedded and building applications and manufacturing devices like networked lighting controls. Battelle is a nonprofit that develops and commercializes technology.

When we found vulnerabilities in the products these vendors produce, our team disclosed them to the vendors. All the vendors were responsive and have since issued patches and software updates to address the flaws we’ll detail here.

After we found the vulnerabilities and developed exploits to test their viabilities in an attack scenario, our team found dozens (and, in some cases, hundreds) of each vendor’s devices exposed to remote access on the Internet. All we did was use common search engines like Shodan or Censys, which are accessible to anyone using a computer.

Once we located an exposed device using some standard Internet searches, we were able to determine in some instances by whom the devices were purchased and, most importantly, what they were using the devices for. We found a European country using vulnerable devices for radiation detection and a major US city using them for traffic monitoring. Upon discovering these vulnerabilities, our team promptly alerted the proper authorities and agencies of these risks.

SMART CITY SCARE

Now, here’s where “panic attacks” could become a real threat. According to our logical deductions, if someone, supervillain or not, were to abuse vulnerabilities like the ones we documented in smart city systems, the effects could range from inconvenient to catastrophic. While no evidence exists that such attacks have taken place, we have found vulnerable systems in major cities in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere. Here are some examples we found disturbing:

- Flood warnings (or lack thereof): Attackers could manipulate water level sensor responses to report flooding in an area where there is none — creating panic, evacuations and destabilization. Conversely, attackers could silence flood sensors to prevent warning of an actual flood event, whether caused by natural means or in combination with the destruction of a dam or water reservoir.

- Radiation alarms: Similar to the flood scenario, attackers could trigger a radiation leak warning in the area surrounding a nuclear power plant without any actual imminent danger. The resulting panic among civilians would be heightened due to the relatively invisible nature of radiation and the difficulty in confirming danger.

- General chaos (via traffic, gunshot reports, building alarms, emergency alarms, etc.): Pick your favorite crime action movie from the last few years, and there’s a good chance that some hacker magically controls traffic signals and reroutes vehicles. While they’re usually shown hacking into “metro traffic control” or similar systems, things in the real world can be even less complicated. If one could control a few square blocks worth of remote traffic sensors, they could create a similar gridlock effect as seen in the movies. Those gridlocks typically show up when criminals needed a few extra minutes to evade the cops or hope to send them on a wild goose chase. Controlling additional systems could enable an attacker to set off a string of building alarms or trigger gunshot sounds on audio sensors across town, further fueling panic.

In summary, the effects of vulnerable smart city devices are no laughing matter, and security around these sensors and controls must be a lot more stringent to prevent scenarios like the few we described.

THE VULNERABILITIES

IBM X-Force Red and Threatcare have so far discovered and disclosed 17 vulnerabilities in four smart city systems from three different vendors. The vulnerabilities are listed below in order of criticality for each vendor we tested:

Meshlium by Libelium (wireless sensor networks)

- (4) CRITICAL — preauthentication shell injection flaw in Meshlium (four distinct instances)

i.LON 100/i.LON SmartServer and i.LON 600 by Echelon

- CRITICAL — i.LON 100 default configuration allows authentication bypass – CVE-2018-10627

- CRITICAL — i.LON 100 and i.LON 600 authentication bypass flaw – CVE-2018-8859

- HIGH — i.LON 100 and i.LON 600 default credentials

- MEDIUM — i.LON 100 and i.LON 600 unencrypted communications – CVE-2018-8855

- LOW — i.LON 100 and i.LON 600 plaintext passwords – CVE-2018-8851

V2I (vehicle-to-infrastructure) Hub v2.5.1 by Battelle

- CRITICAL — hard-coded administrative account – CVE-2018-1000625

- HIGH — sensitive functionality available without authentication – CVE-2018-1000624

- HIGH — SQL injection – CVE-2018-1000630

- HIGH — default API key – CVE-2018-1000626

- HIGH — API key file web accessible – CVE-2018-1000627

- HIGH — API auth bypass – CVE-2018-1000628

- MEDIUM — reflected XSS – CVE-2018-1000629

V2I Hub v3.0 by Battelle

- CRITICAL — SQL injection – CVE-2018-1000631

THE FIXES

Smart city technology spending is anticipated to hit US$80 billion this year and grow to US$135 billion by 2021. As smart cities become more common, the industry needs to re-examine the frameworks for these systems to design and test them with security in mind from the start. In light of our findings, here are some recommendations to help secure smart city systems:

- Implement IP address restrictions to connect to the smart city systems;

- Leverage basic application scanning tools that can help identify simple flaws;

- Safer password and API key practices can go a long way in preventing an attack;

- Take advantage of security incident and event management (SIEM) tools to identify suspicious traffic; and

- Hire “hackers” to test systems for software and hardware vulnerabilities. There are teams of security professionals — such as IBM X-Force Red — that are trained to “think like a hacker” and find the flaws in systems before the bad guys do.

Additionally, security researchers can continue to drive research and awareness in this space, which is what IBM X-Force Red and Threatcare intended to do with this project.