Download / Unlock / Ride / Park Properly

Tommaso Bonino reports from a city that is looking beyond smart-docks and smartbikes and concluding that the best policy for bike-sharing might be smart-regulation

I n recent years, bike-sharing has undergone some radical changes: the scheme got rid of docks, the business went Chinese and the local authorities are happy to be spoon-fed by operators. This has allowed bikesharing systems to record momentous increases in effectiveness.

The truth is, in fact, much more complex: free-floating bike-sharing has generated chaos in cities, especially where road networks are poor or undersized and where the number of private vehicles is high; Chinese companies have highlighted a technology – the “smart-lock” – which is not their exclusive and the local authorities have had to regulate a sector that was believed to be able to do so on its own.

Increases in use, however, have been significant, not only thanks to new technologies or to the arrival of new operators, but also – and in the writer’s opinion in most part – because the bicycle has returned to its natural role and perspective. The latest generation of bike-sharing schemes makes the bike available, safe (because of integrated lights), secure (because of the lock and the GPS system), friendly and trendy. The inner cyclist in each of us – when we make a home-work trip less than 5 km long or when we need to move during the day, at work or for leisure – now has the possibility to access a bike without worrying about maintenance and theft, just by activating an app and paying by credit card.

"The latest generation of bike-sharing schemes makes the bike available, safe (because of integrated lights), secure (because of the lock and the GPS system), friendly and trendy"

FROM DUMB TO SMART TO…

The “dumb-bikes” scheme (born in the Netherlands in the 1960s) has evolved into the “dumb-docks” scheme (where bikes were linked to stations, without intelligence), then into the “smart-docks” scheme (where stations were recognising bikes and users, collecting data on usage as well) and then finally into the fourth generation: the “smartbikes” scheme, where bikes are stand-alone, free-floating, linked to the users’ smartphones, with no need for infrastructure.

The “smart-docks” systems in London, Paris and New York, financed by the public and/or by large companies, following those characterised by “dumb-docks”, are well known to all; the sequence “SIGN UP/SWIPE OUT/RIDE/DOCK” has been the subject of many rides – London has recorded 600,000-1,100,000 hires/ month in 2017 and has benefitted from £11 million (€12.47 million) of customers income, £6.4 million from Santander and £3.6 million from Transport for London (TfL).

Now the description has changed a bit and has become “DOWNLOAD/ UNLOCK/GO”; the parking phase at the end of each trip is less cared for. The local authorities play a minor role: no resources are needed and the regulation is minimal, just referring to the common circulation regulations.

Bologna would have liked to have moved on from the model of the “dumb-docks”, already active for at least 10 years, providing some 200 bicycles which have collected over time about 6,900 members. As the “dumb-docks” system do not generate sufficient usage data, Bologna would have liked to set up a scheme of “smart-docks” while investing significantly in cycling, in the early 2010s. However, setting up a system like the one in London would have cost the city at least €5 million a year and Bologna is not as attractive as London, or New York, in the eyes of the investors who wanted to be a sponsor of the initiative. Given the lack of such a budget, Bologna waited, paying attention to the evolving market, yet maintaining a growing commitment to cycling – for example by adopting its “Biciplan” (a plan for cycling trips and infrastructure, targeting over 10 years in the future).

As a result of what was experienced in other countries, not exclusively China, we understood that with a significantly lower budget it would be possible to take advantage of the newest technologies and to overcome the existing system of bike-sharing. In March 2017, the city council allocated €800,000 per year for six years to the project and SRM – the local authority for transport – launched a tender through a competitive dialogue to find an operator on the market who could organise a free-floating bike-sharing system in Bologna, incentivised by means of the parking fees.

The competitive dialogue, by definition (Directive 2014/24/EU), helps local authorities find what they need (“Contracting authorities shall open, with the selected participants, a dialogue the aim of which shall be to identify and define the means best suited to satisfying their needs”). Fares incentives motivate an individual to perform an action; the instrument of incentive structures is central to individual decision-making within a larger institutional environment.

The planning of the award procedure was conceived in detail:

- An adequate tender scheme was designed;

- An incentives’ structure was to be provided to the operator and to the users;

- The service obligations had to be clearly defined;

- Data from both parts have to be made available;

- Revenues are known and shared if beyond a defined threshold.

"The fares for bicycle use will work as an incentive: users who park at a station spend less, those who park free-floating spend more"

MEETING ACTUAL NEEDS

The tender was launched in June 2017. The data collected in the city thanks to initiatives to promote cycling organized in previous years (the “European Cycling Challenge” and “Bella Mossa”, both born under the patronage of the European Commission) were made available to competitors so that they could submit solutions and projects as close as possible to the real needs of city-users. The tender was immediately appealed in the administrative court by an Italian company, already active on the market with a “smart-docks” system that was not designed for free-floating. It deserves to be underlined that London’s first “Dockless Cycle Hire” Code of Practice was launched by TfL in July 2017 and was updated in September 2018.

Three companies expressed interest: two European and one Chinese (Nextbike, Velospot, Mobike). Following an interesting debate – and after winning the appeal before the administrative court – SRM awarded the service to an Italian company, licensee of the Mobike brand (whose name is IDRI BK). The fee was reduced by 50 per cent, to €400,000 per year, VAT included. The first Mobike bike appeared on the streets on 19 June 2018.

Some 2,500 bicycles are expected to be in service, with the operator committed to creating 240 “light” stations called “Mobike HUB”, equipped with so-called “beacon” sensors, more accurate than GPS, that allows users to recognize if a bike is parked in the station. Stations are indicated on the smartphone app as well. The fares for bicycle use will work as an incentive: users who park at a station spend less, those who park free-floating spend more.

The compensation from the municipality covers the service obligations imposed by the contract with regards to maintenance, replacement and repositioning, all these operations being regulated through quality indicators. The maximum fares to the public are regulated and also the maximum level of average revenues per journey is set to a threshold beyond which the contract has to be rebalanced in favour of SRM. In addition to that, the assignee is obliged to refer to users granting a point of contact in the city centre, to make the usage data available and to provide the city with 300 e-bikes (Bologna will be the first city in Italy to host Mobike e-bikes next Spring).

Mobike in Bologna is committed to delivering a mobility service, not just in deploying a bicycle fleet. SRM has selected a partner whose commitment is to satisfying a significant amount of users in order to turn urban modal-share towards a more sustainable balance.

The first few months of operations have shown very interesting results:

- The growth in the use of the service was initially proportional to the distribution of bicycles in the city, then fast and consistent; with the advent of the school year four average uses per day per bicycle in service were exceeded (this means more than 10,000 hires/day);

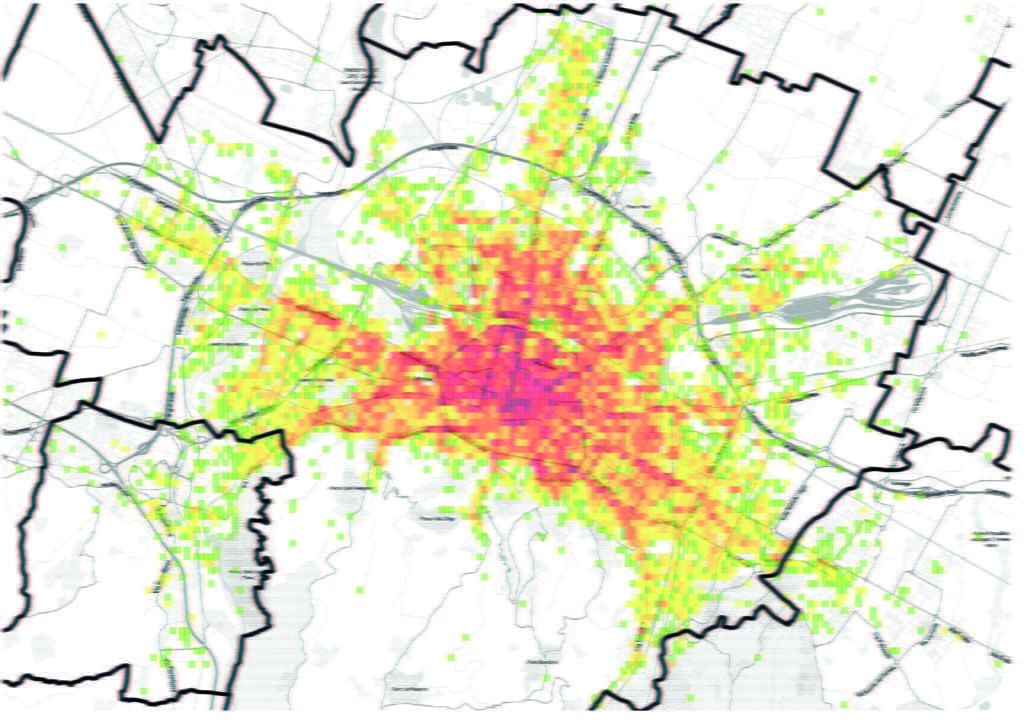

- The bicycles’ collection and return data made it possible, after just two months, to redesign the area covered by the service so as to serve the zones that had best responded to the service offer;

- 91 per cent of the trips lasted less than 30 minutes, the unit of time that was taken as a reference for the fare.

The collected data is shared among the parts and the first impressions are positive - SRM has had no problems in accessing them and no issues about commercial use and/or privacy have been noted.

The appreciation of city-users, citizens’ representatives and tourists was immediate and surprising; social networks promptly welcomed Mobike bicycles as a main feature on the streets.

USE AND MISUSE

In addition to these gratifying numbers, there have been the inevitable issues of misuse and vandalism of bicycles to report. Some bicycles have been parked on the sidewalks and alongside public transport stops, undermining in particular the safety and confidence of people with disabilities; some bicycles have been painted and some burned, in some cases they have been parked in private spaces, making them unavailable for other potential users. For the time being, these episodes have been limited to less than 10 per cent of the overall size of the fleet, thus respecting what was planned so that the provision of the service would not be compromised and costs would not increase beyond the threshold of acceptability.

Finally, the old bike-sharing system has been reallocated towards specific spots in the city, where “dumb-docks” can still provide a benefit to city-users, notably at minor urban railway stations.

FYI